You are here

Government Intervention: Gold and Long-term Interest Rates - by Michael Bolser

Abstract ![]()

In previous work I drew attention to the link between the rapid growth of interest rate derivatives [IRDs] at Chase and Morgan subsequent to an unprecedented gold market preemptive selling episode in 1996. This report will further explore the likely interventional reasons behind this extreme interest rate derivatives growth. In addition, an important 1998 Federal Reserve consultant's publications that describe exact methodology needed to enforce the government's long-term interest rate policies are reviewed. Also the report shows preliminary evidence that since Summer 2003 the long interest rates appear to be under the controlling influence of those Federal Reserve policies. Finally, issues threatening the gold and interest rate interventional operations of the Federal Reserve are briefly discussed.

Background

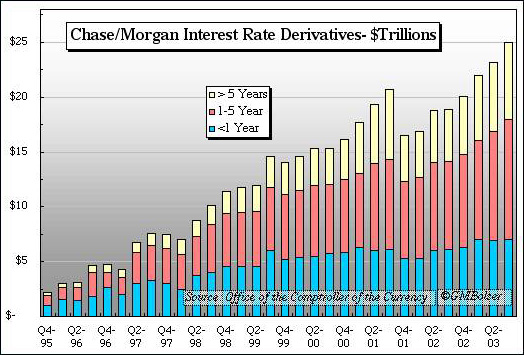

In Preemptive Selling of Gold: The Bigger Picture, a conspicuous link was shown between Chase Manhattan Bank's doubling of their interest rate derivative position just weeks after the extreme 4.22 standard deviation COMEX gold preemptive selling event in June 1996. Chase moved to boost their IRDs only after gold's 200-day moving average had been successfully breached to the down side. A short time later, JP Morgan joined in with what has now become a $25 Trillion IRD colossus (Sept 2003, Office of Comptroller of the Currency).

These two financially historic events can be seen as the principal features that enabled the deliberate construction of the various asset bubbles that seem now to be increasingly fragile, requiring more and more government intervention to sustain them (this includes an artificially driven DOW, see: Repurchase Agreements and the DOW. This on-going study is updated daily at: http://www.lemetropolecafe.com/index.html ).

That the mid-nineties gold intervention was extreme has recently been further buttressed by the work of Jim Turk in: More Proof , wherein he reveals that Her Majesty's customs records indicate that in 1997 2,600 tonnes of gold were dishoarded from the US and UK (likely as deliveries for the preemptive selling episode earlier in June of 1996). Gold Fields Minerals Services [GFMS] weakly disputed this direct customs records finding with no rebuttal of the facts. Their failure to report to the gold community at large this massive 1997 dishoarding stands as a continuing embarrassment to the statistical arm of the World Gold Council.

A further damning piece of evidence to GFMS, which continues to claim only 4,000 tonnes of gold loans, can be found in the Bank for International Settlements (keyword: Triennial Survey Statistical Annex 2001). This report details all central banks derivative activity including gold forward sales and swaps. In table E.49 on page 81 of the report are results that reveal that the central banks of the BIS have sold forward or swapped over 15,000 tonnes of their gold bullion. A detailed commentary on the topic Gold Derivatives: Moving Towards Checkmate was presented by Reginald Howe in December 2002. Contrary to the popular gold community press this BIS data suggests that the central banks no longer have 32,000 tonnes of unencumbered gold.

The government's foundational reasoning behind the mid-nineties gold market intervention can be found in Gibson's Paradox Revisited: Professor Summers Analyzes Gold prices at Goldensextant.com. In a scholarly 1988 article (Gibson's Paradox and the Gold Standard), Summers argues that to control the general price level (as indicated by interest rates) one needed to control gold, although he did not put it so provocatively:

Determination the general price level then amounts to the microeconomic problem of determining the relative price of gold.

The paper presented long-term evidence to prove the relationship between real interest rates and the gold price. It was a short step from this finding to the idea that to control one of the metrics you also controlled the other. A plan was born.

It is difficult to overstate the importance that government control of gold and its link with to long-term interest rates has played in the modern economic era. It was the beachhead from which all other meaningful market events flowed. Once the watchdog role of gold had been removed, interest rates were free to be systematically lowered and massive credit expansion could occur without threat of dangerous interest rate volatility where today we see $3 Trillion in mortgage securities residing in Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac portfolios and the already towering general credit access which keeps on expanding. But capping gold through sales below market levels is only one aspect of the scheme-the other is controlling the interest rate curve.

Adam Hamilton's review: Long Bond Assassinated! Touches on the 2001 removal by the government of a decades-old financial instrument, doubtless to avoid the threat of low auction bids (and consequent high long-term interest rate spikes). The government then announced a buy-back program that had the distinct effect of capping interest rates in the long bond. PIMCO, one of the largest bond specialists in the financial world, had this to say:

"At the end of the day it's Uncle Sam effectively trying to reduce long-term interest rates." - Paul McCulley, Pacific Investment Management Co., October 31, 2001

It is often repeated that the Fed controls short-term interest rates but the "market" controls the long end of the interest rate curve. Is the Fed really only a spectator in the important arena of long-term interest rates?

The Fed's toolbox

Several papers written by Federal Reserve consultants lay out the various tools and methods available to the Fed in its push to intervene in the bond markets in order to enforce its long-term interest rate policies. One of these: SHORT RATE EXPECTATIONS, TERM PREMIUMS, AND CENTRAL BANK USE OF DERIVATIVES TO REDUCE POLICY UNCERTAINTY P. A. Tinsley (September 1998) contains very detailed information on just how the Fed can go about achieving a reduction in "policy uncertainty".

Abstract: The term structure of interest rates is the primary transmission channel of monetary policy. Under the expectations hypothesis, anticipated settings of the short-term interest rate controlled by the central bank are the main determinants of nominal bond rates. Historical experience suggests that bond rates may remain relatively high even if the short-term interest rate is reduced to zero, in part due to term premiums reflecting uncertainty about future policy. Term spreads due to policy uncertainty may be reduced by central bank trading desk options that provide insurance against future deviations from an announced interest rate policy. [Emphasis added]

Professor Tinsley, Cambridge University, goes on with the following statement that well summarizes his paper's objective:

In critical episodes, such as a persistent recession where the short rate may be driven near zero, historical experience suggests long-term bond rates may remain well above zero. This paper indicates derivative securities issued by the trading desk may tighten connections between policy intentions for the short rate and current long-term interest rates. Discussion is directed principally at policy options to influence nominal yields on Treasury securities. [Emphasis added]

And this passage where he lays out the Fed's rate enforcement methodology:

There are two major differences in the present proposal from current operating procedures. First, instead of disclosing only the current policy setting of the short-term rate, the central bank also indicates one or more explicit upper or lower boundary points on the yield curve that will be enforced by future policy, presumably at the short end of the term structure. Second, the credibility of the central bank policy is enforced by binding contractual arrangements with private sector agents, who will be compensated for any future deviations from the policy terms designated in the contingent contracts. [Emphasis added]

The Fed would, under Professor Tinsley's suggestions, hire agents to enforce "upper and lower boundary points on the yield curve". He then goes on to describes exactly how this would occur in section IV. Policy Puts:

Bond puts and interest rate calls

To enforce a floor on near-term bond maturities, derivative contracts that provide explicit policy signals over the next two years include the writing of short-horizon bond puts. For example, suppose the expiration date of the options is three months, and put contracts are written on forward 9-month and 21-month bonds with a unit strike price of $1. In three months, the trading desk will be obligated to buy 9-month and 21-month Treasury bonds from option owners at the strike price of $1 or, more likely, will settle in cash the difference between $1 and the existent bond prices.

In order to make this kind of intervention in a very large bond market possible, the professor makes an important note that a large source of liquidity is necessary:

Altering fundamentals

In principle, the existence of well-developed derivatives markets increases the liquidity of asset markets and, thus, tends to reduce bid-ask spreads on underlying assets, Fedenia and Grammatikos (1992) [Emphasis added].

...policy use of derivatives can alter the perceptions of economic fundamentals held by market agents. Given that the central bank has a monopoly on the supply of the domestic currency, it has the capacity to directly purchase or write options against any proportion of the outstanding Treasury debt. Private sector agents who exercise [bond] put options written by the trading desk are paid in the domestic currency [emphasis added].

It may now be better appreciated why Fed agent JP Morgan Chase constructed its towering $25 Trillion interest rate derivatives position beginning in 1996-seemingly oblivious to the risks. It is not unreasonable to conclude that it was done to create a source of needed liquidity to control the interest rate curve.

Indeed, Tinsley isn't alone in the idea of central bank intervention in the long-term interest rate arena when he referred to this quote:

It should not be beyond the power of a Central Bank (international complications aside) to bring the long-term market-rate of interest to any figure at which it is itself prepared to buy long-term securities." Keynes (1930, p.371)

Is Tinsley alone today?

One could dismiss a single highly technical paper suggesting Fed intervention in the long rate market but there is another even more explicit article by Clouse, Henderson et al and co-authored by Tinsley posted at the fed's website: Monetary Policy When the Nominal Short-Term Interest Rate is Zero

Abstract: ... This paper also examines the alternative policy tools that are available to the Federal Reserve in theory, and notes the practical limitations imposed by the Federal Reserve Act, The tools the Federal Reserve has at its disposal include open market purchases of Treasury bonds and private-sector credit instruments (at least those that may be purchased by the Federal Reserve); unsterilized [sic] and sterilized intervention in foreign exchange; lending through the discount window; and, perhaps in some circumstances, the use of options. [emphasis added]

The authors present their thesis of long-term interest rate intervention by the Federal Reserve's open market operations in section 4:

4. Policy Actions in Longer-Term Treasury Securities and in Options on Treasury Securities

As shown in Section 2, historical experience in the United States and recent experience in Japan suggest that longer-term nominal interest rates may remain elevated and thereby hinder economic recovery even when the short-term nominal interest rate is zero. This section explores two policy actions the Federal Reserve may undertake to reduce longer-term Treasury rates: the purchase of Treasury bonds and the writing of options on Treasury securities.

4.1 Open Market Operations in U.S. Treasury Bonds

If the Federal Reserve has driven the nominal short-term Treasury rates to zero, it could switch from purchasing Treasury bills to purchasing Treasury bonds. The effects on the monetary base are the same whether bills or bonds are purchased. Indeed, the purchase of Treasury bonds can be seen as being the combination of two transactions: the open market purchase of Treasury bills and the exchange of Treasury bills for Treasury bonds. ...Here we focus on possible direct effects on bond rates.

The above references support the theoretical policy basis for Fed intervention in the long-term interest rate markets. Let's take a closer look at JP Morgan's actual position in interest rate derivatives as of Sept 2003.

Note the large move in the third quarter of 1996 immediately following a huge COMEX gold preemptive selling episode. The Q4 2001 dip in IRDs is the netting of mutually held contracts produced by the merger of Chase and Morgan. Here, then, can be found the needed interventional liquidity referred to by Tinsley et al. in their bond market interventional thesis.

Current intervention in long-term interest rates

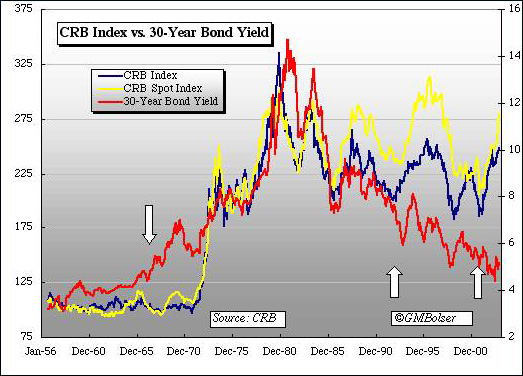

Is the long-term interest rate currently under government intervention today? Let's take a look at past conditions of divergence from the norm and then zoom in on this year.

This familiar profile recalls the high inflation of the early eighties but more to our interest, it reveals that there are three periods of diversion from the well-established link between the CRB indexes (aggregate and spot) and the long-term interest rate. Each of these periods of CRB/long-term interest rate diversions can be associated with gold market intervention.

First, when the London Gold Pool was disbanded in the late sixties, then when preemptive selling began in the early 1990s and again today when the pace of gold intervention has accelerated with the rising gold price. Even before the gold price took off in the early 1970s the long-term interest rates were rising, doubtless as investors caught scent of the unsustainable macroeconomic policies of the Johnson Administration and most importantly the deficits and bills that came due from the expensive Viet Nam War.

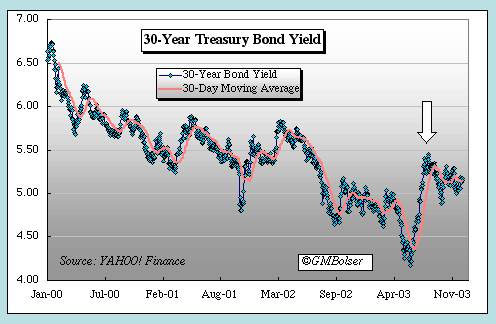

Clearly today's Fed would not want a repeat of this dreadful pattern so they have a powerful incentive to act. A closer examination of the long-term interest rate can be seen below:

We see our now all-too-familiar steep drop in long term bond rates halted in mid April as the bond market started to fall badly and rates rose steeply. Rapid moves such as this play havoc with interest rate derivatives and business portfolios linked to those rates (Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac) are the first to suffer. Then late this Summer it appears that the "Policy Puts" of Professor Tinsley et al may have been invoked in earnest to cap the rates just above 5%.

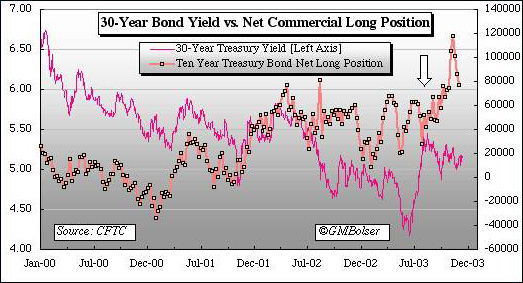

Looking further at the CFTC net commercial long positions in the ten-year Treasury bond we see direct evidence of this intervention:

The commercials include JP Morgan Chase as their standard bearer and they reacted a bit slowly at first to the rising April yields but accelerated their long positions until the rate was capped as it remains today. Also, once the long-term interest rate cap had been installed, the volatility in rates has been kept very low. This low volatility is a hallmark of intervention as the cost of options is directly related to the volatility index and therefore would be important for the Fed's agents to reduce to an absolute minimum in order to make their interventions as cost-effective as possible.

Sequestering Treasuries Overseas: The Fed's Compartments

Getting US overseas friends to buy treasuries in order to keep long-term interest rates down is a formal Fed plan. Indeed, earlier this year the Fed added currency intervention announcements (Japan) to its mix of intervention.

Pundits often forecast dire consequences when foreign held treasuries eventually come home to roost. But will this ever happen? This is ever-so-slowly showing signs of occurring, but Japan holds the lion's share of these financial instruments and due to formal Fed agreements with them and to US/Japan geopolitical realities, Japan is unlikely to ever sell their hoard of US debt instruments. This condition is also a form of market intervention, since Japan is not acting in its best financial interest in the face of the falling dollar. The sequestration effectively lowers the aggregate size of the long-term treasury security pool and aids in the Fed's interventional policies. The long-term interest rate market isn't as big as it seems when Japan's holding intentions are factored in.

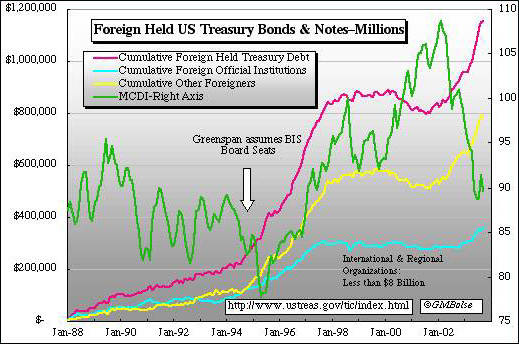

The overall picture of foreign held Treasury debt is none-the-less still a frightening spectacle:

The MCDI is the major currency dollar index. In order to fill dwindling demand for US treasury bonds and quell the rising long-term interest rates, Japan and other compliant US partners buy US Treasuries (sometimes against their best interests, as mentioned above). Since the middle of 2001 the pattern of this foreign treasury buying has taken on an exponential growth appearance as the stress on long-term interest rates continues to build.

It is instructive as well to examine the flat period beginning in 1997 which was a period of successful gold market domination by the Fed's agents (JPM, et al) that featured quiescent and falling gold prices and a rising MCDI. They may have been the strong dollar policy's best years. However, when the gold price began rising post Washington Agreement in the middle of 2001, things began to deteriorate in earnest.

Achilles Heels

In the end, the Fed isn't invincible. The great experiment of un-backed fiat money that began in 1971 is after all, just an experiment. Their war on gold, long-term interest rates and inflationary expectations has many facets and they have many weapons, plus the Federal Reserve has everything to lose if they fail.

In the Clouse, Henderson, Tinsley article posted at the Fed's website (see link above) the following table of Federal Reserve debt purchasing weapons can be found:

6 Purchasing Debt of U.S. Financial Services Institutions and the Private Sector

Table 6.1 Types of Financial Assets That May be Purchased by the Federal Reserve*

Obligation: Assets The U.S. Government Debt

14(b)(1) All U.S. Treasury securities and securities which are fully guaranteed by the United States 14(b)(2) U.S. agency securities and those securities fully guaranteed by U.S. agencies.Private Sector Debt

14 cable transfers and bankers' acceptances and bills of exchange of the kinds and maturities ... eligible for rediscount." * * *

14(c) \bills of exchange arising out of commercial transactions ..."

13(4) Bills of exchange payable on sight or demand which grow out of the shipment of agricultural goods. * * *State and Local Governments

14(b)(1) bills, notes, revenue bonds and warrants used in anticipation of taxes or assured revenues * * *

Foreign Government Debt

14(b)(1) Direct obligations and securities which are fully guaranteed by a foreign government or agency thereof.

* The Federal Reserve may also purchase gold subject to the Gold Reserve Act of 1934.

* * As noted in footnote 73, the phrase \of the kinds and maturities ... eligible for purchase" in the _rst paragraph of section 14 may apply to both bankers' acceptances and bills of exchange or just to the latter.

* * * Subject to maturity limitations.

This is a powerful array of government purchasing capacity. For example, if one or more of the Fed's primary dealer trading houses gets overextended in their derivatives positions the Federal Reserve can simply guarantee the losses, according to the above information. The IRD colossus at JPM would be included in such guarantees. This reality also may prevent a COMEX short covering, derivatives-based rally in precious metals but the COMEX precious metals sector is but a small cog in a World Wide precious metals market. However, smaller US players on the short side who are not in the inner circle of Fed friends may find themselves left in the lurch. Barrick Gold comes to mind.

Moreover, the world balance of financial confidence rests upon the dollar and long-term interest rates. External pressures working against them tend to leak through the Fed's many compartments into the open as we see (above) in the required foreign purchases of US treasuries that are now becoming very conspicuous.

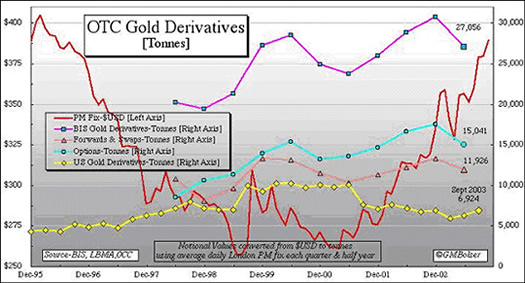

A crucial component in the Fed's overall interventional plans is the continued suppression of the gold price. The above chart shows the aggregate position of BIS and US bank members in gold derivatives expressed in tonnes, current through September 2003.

There is strong evidence that the supply of central bank gold needed to sell in this effort is getting short. Indeed, when selected central bank annual reports are examined closely, one finds no bullion remaining in their vaults although gold derivatives ("receivables") adorn their balance sheet (Canada, Australia). At some point, some foreign central banks may balk at further gold donations to a futile cause of Fed intervention (Their derivatives losses may not be covered by their own governments). The weight of history holds no success for un-backed, fiat money.

Should that happen, a spiral upwards (perhaps into the thousands of dollars per ounce) would visit the gold price as it separated in a big way from the dollar. As a result, the entire interventional superstructure of both interest rates and precious metals conducted by the Federal Reserve for the last ten years would come undone-what Sir Eddie George referred to during the Washington Agreement as "The Abyss".

The worsening trade imbalance (led by petroleum expenditures) helps to accelerate the fall in the MCDI. While the Fed has cajoled, wheedled and pressed the President repeatedly to confront the Chinese for aid in de-linking their currency (Yuan) from the dollar, the Chinese continue to oddly act in their own best interest and keep the Yuan's peg even as they extract more and more geopolitical concessions from a weaker and weaker President. Incidentally, the long-term Chinese plan with its dollar/Yuan link seems to allow the Yuan to become even more competitive with the Euro, giving them an overwhelmingly strong import advantage and ultimate complete integration into Europe's distribution apparatus as they have successfully achieved in the US.

Energy

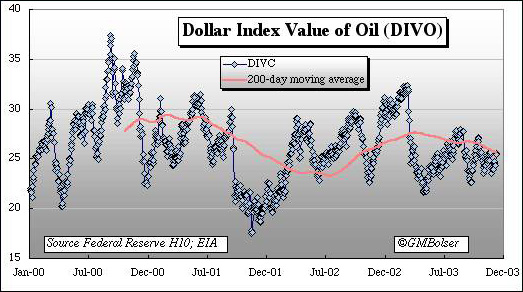

Finally, perhaps the most important area of weakness in the Fed's war on inflationary expectations, gold and long-term interest rates is energy. Below is the currency-adjusted price of crude oil.

Observations of commodity prices must be made in the light of their dollar-adjusted values (Crude oil price X MCDI ÷ 100). This is undoubtedly the practice of energy producers who import to the US. We see from this chart that the 200-day moving average is nearing a cyclical turning point back upwards. In addition, the Russian Federation and Saudis have recently developed closer ties and are likely watching this data carefully, mindful not to allow too low a return for their principal export product. Given the falling MCDI the current moving average activity means that, barring a huge anomaly of unexpected supply, $32/bbl should be considered a floor price since just to maintain a flat DIVO pattern, the oil price would have to rise in compensation to the falling MCDI. But as critical as petroleum is, natural gas is even more so.

This is why Alan Greenspan recently spoke at length about natural gas. Without a large storage capacity similar in size to the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, natural gas prices are therefore far more volatile and immune from the Fed's controlling forces, as we have just seen when natural gas prices just breached $7. Experts are sounding major alarms as Canadian natural gas production steeply falls to record lows. The ripple effects of this price rise in the industrial arena are not inconsequential and the Fed shows all the signs of serious concern because of the negative effect on inflationary expectations and the increasing pressure on long-term interest rates.

They know they are in trouble with energy. Continued threats to re price OPEC oil in Euros is an on-again, off-again affair but serves to further remind the Fed that their many Achilles Heels are beginning to pose tempting targets for aggressive speculators.

Michael Bolser

2215 Summit View Drive

Valrico, Florida 33594

The writer wishes to thank Bill Murphy and Chris Powell of the gold Anti-Trust Action Committee for their support http://www.gata.org/

Thanks also to Frank Veneroso for the PA Tinsley reference.